Maritime Trade

Episode 3

The golden age of sail gave way to a world of global trade, where gold and silver could be sailed internationally for vast profit. Explore how the money made from and used for this trade shaped British history.

Britannia is a figure that has become synonymous with our nation. She has had many guises but, for the Royal Mint, she has developed into the figure of a woman, often classically attired, complete with robes, Corinthian helmet, shield and trident. Yet, there are many other forms and places that she might be encountered, whether in the name of companies, on pub signs or in art, she has become a short-hand visual to represent the nation. Her link with the sea may sometimes be subtle, but it is usually present and often obvious. But how did this develop and how did she end up becoming the female personification of a maritime nation? This is one of the questions we will answer throughout this episode. But first, we are going to dive in to a few more concepts of Britannia.

Christopher Ironside sought to create a fresh image of Britannia, one that was less stern and forbidding than that which had appeared on coins struck during the reign of Queen Victorian. His take on the icon first appeared on the new 50p piece in 1969 and can still be found in our change today.

Britannia has been a political cartoonist's dream, and numerous political figures, such as Gordon Brown and Margaret Thatcher, have been dressed up as her over the years in the cause of satire.

The Peace of Breda medal, struck to mark the negotiations which brought to an end the Second Dutch War in 1667, portrayed an overtly maritime Britannia. Seated with her backs to cliffs and looking out to sea, she surveys the English navy.

Trials for the new copper coinage of Charles II were produced in the 1660s. Some contain the inscription I CLAIM THE FOUR SEAS in latin, but this never appeared on the new coinage when it was officially issued in 1672. A number of maritime setbacks during the war with the Dutch, including a raid on the English fleet in the Medway in 1667, made the claim feel quite hollow.

The first official copper coinage was struck in 1672. The new halfpennies and farthings featured a striking image of Britannia, but, on the coinage, as yet not an overtly maritime figure. Evidence from diarists Samuel Pepys and Sir John Evelyn would seem to suggest that the image of Britannia used on these coins was based on Frances Stuart, Duchess of Richmond.

Throughout the later 18th and early 19th century, the figure of Britannia was used on medals to mark naval victories, such as in this example for Admiral Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile in 1798.

George William DeSaulles’ design for the florin of Edward VII featured an image of Britannia which was based on Susan Hicks Beech, the then Chancellor’s daughter.

In 1987 the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Lawson, issued a new bullion coin to counter the growing popularity of the South African Krugerrand. The image of Britannia designed by the artist Philip Nathan was chosen for the new coin series, which was named after her.

The Royal Mint Museum’s collection contains a large amount of artwork for coin competitions from the last century. This includes numerous designs for the figure of Britannia, like these from the decimalisation, many of which never made it onto the coinage.

Our guests in this episode were Kate Eustace, Dr Barrie Cook (British Museum) and Dr Kevin Clancy (Royal Mint Museum). Click here to find out more about them.

The personification of a nation as a woman date back to the era of Roman imperial expansion with Gallia, Dacia, Provincia and Africa amongst those territories which appear as female figures on the coinage. Britannia features several times on the coinage, the first type appearing under Emperor Hadrian. The coin, which was struck in Rome in c. 119, features Britannia holding a spear and seated on rocks, or possibly a wall, with the inscription BRITANNIA. Hadrian would visit Britain in 122, and his famous wall was begun as a result.

The use of the figure of Britannia in Britain would lapse after the fall of the Roman Empire but found renewed life in the Elizabethan period in the works of John Dee. A mathematician and astrologer, Dee was one of the major forces of the age and was obsessed with the idea of a British Empire based on maritime power. This formed the theme of his book, General and Rare Memorials Petrayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation (1577), the cover page of which shows a kneeling Britannia entreating Elizabeth I to strengthen the Navy. His version of Britannia is significant as her link to the sea is overtly established for the first time, an association which was developed under the reign of James I by the likes of the antiquarian William Camden and the scholar John Selden. Amongst the evidence that Selden uses to justify James I claims to the sea are the Roman coins of Emperors Antonius Pius, Commodus and Hadrian which depict Britannia. He misinterprets the rocks upon which the Roman Britannia stands as waves and uses this to illustrate the Roman imperial claim to dominion over the British seas.

The Stuart monarchs used Britannia to try and position themselves as masters of the sea. The outbreak of the war against the Dutch in 1665 led to pattern farthings and halfpennies of that year showing Britannia on the reverse with the legend ‘I claim the four seas’ in Latin. She was used again on a medal of 1667 struck to mark the Peace of Breda which brought an end to the Dutch war. The medal depicts Britannia seated at the base of cliffs holding a spear and shield bearing the crosses of St George and St Andrew whilst looking out to sea and surveying her fleet. In 1672 she achieved official status by appearing on the reverse of the new copper halfpennies and farthings, although the inscription claiming mastery over the seas as dropped, most likely as a result of naval setbacks during the war with the Dutch. From the reign of Charles II onwards Britannia would appear on the reverse of at least some of the denominations of the coinage of every monarch.

The figure for Britannia on the new copper halfpennies and farthing of 1672 is often said to be based on Frances Stuart, Duchess of Richmond. The design caused a stir in society at the time, the noted diarist Samuel Pepys recording in 1667 ‘at my goldsmith’s did observe the King’s new Medall where in little there is Mrs Stewarts face as well done as ever I saw’.

Away from the coinage Britannia reflected the growing power of the British Empire and British trade, with images of Britannia in colonies around the globe emphasising British imperial supremacy. The notes of Ceylon in the 1840s show her gesturing towards an elephant, palm trees and the sea and, for notes of the Bank of Bengal, she is seen accepting the fruits of the Empire from a cornucopia offered up by a kneeling Indian woman. The influence of Empire is also felt on images of Britannia used in Britain. In 1886 a map by Captain Colomb showed her seated on a globe supported by Atlas, gazing down on the people and creatures of the Empire.

The First World War aroused Britannia’s martial character, a defiant Britannia appears on the ten shilling notes and her helmeted head on national savings stamps. Perhaps the best known and most poignant example of Britannia comes from Eric Carter Preston’s design for the memorial plaques given to the next of kin who died during the First World War. The sombre figure of Britannia walks with her head bowed beside her lion, a wreath to the fallen held out in her hand.

The accession of Edward VII in 1901 offered an opportunity for a fresh approach. The florin was chosen as the vehicle for a new Britannia design which was entrusted to the Mint engraver George William De Saulles, who based his figure on a real model, the 17-year-old daughter of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Susan Hicks-Beach. The move was not without some controversy and prompted a question in the House of Commons as to whether there had been an open competition. The design was not, however, popular and was abandoned in 1911. Britannia on the penny was remodelled at the start of the reign of George VI by the Royal Mint’s Charles Walter Coombes. The design depicted Britannia seated, holding a trident and shield, with a lighthouse in the background and was retained on the penny for the new reign in 1952, remaining on the coinage until decimalisation. When in 1968 Britannia it appear that Britannia would not appear on the new decimal coins questions were asked in the House of Commons and she was reinstated on the reverse of the new 50p piece issued the following year.

Britannia continues to be an important popular figure, often used at times of national crisis and celebration, such as in the patriotic euphoria at the of the Falklands War in 1982 when the Prime Minster, Margaret Thatcher , was associated with Britannia by newspaper editors, cartoonist and political commentators. Although Britannia disappeared from the nation’s new circulating coin designs in 2008 she still appears on gold and silver coins that bare her name. The first £100 gold Britannia appeared in 1987 when the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Lawson, gave consent to the new gold coin. The winning design by Philip Nathan was reminiscent of George William De Saulles’ 1902 Britannia, with the wind swept figure clutching a shield and an olive branch.

Episode 3

The golden age of sail gave way to a world of global trade, where gold and silver could be sailed internationally for vast profit. Explore how the money made from and used for this trade shaped British history.

Episode 4

Whether sailing, trading or something less legitimate, those who lived and worked on the seas expected payment for their labour. How would sailors have been paid, and more importantly when?

Episode 5

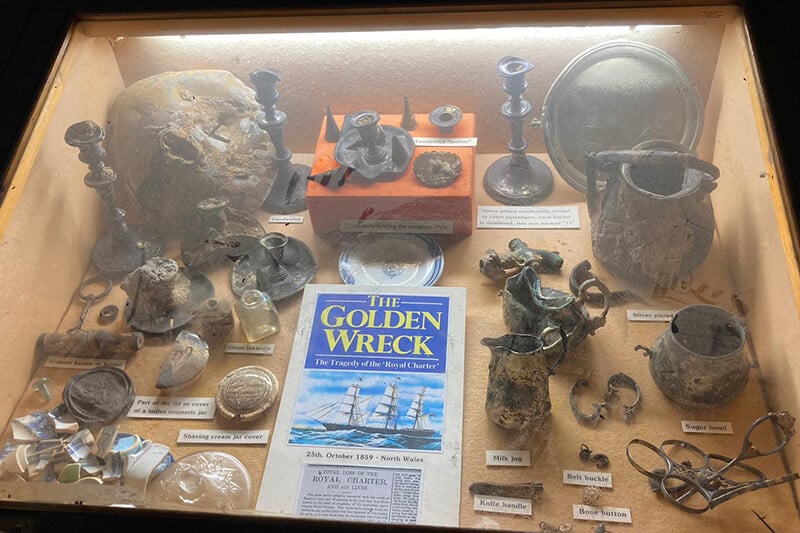

The allure of shipwrecks has drawn treasure hunters and historians alike, but what happens to the cargo they carry? This episode uncovers what happens when gold and silver are recovered from beneath the waves.