Cautionary tales

Do you ever wish you could make yourself a big pile of coins to spend on whatever you would like? For as long as there have been coins, criminals have been trying to do just that! These people are called counterfeiters and the fake coins they make are called counterfeits. Here in the Museum we have many objects which tell us the stories of these crafty counterfeiters and their work. Can you tell which of these coins is a fake?

Robert Schmidt

Our collection contains this pair of counterfeit dies from 1891 which would have been used to press the designs onto fake coins. In 1977 the Museum’s Librarian and Curator became curious about the origin of these objects. Using the date from the ticket attached to them, he searched through The Times newspaper for notable counterfeit cases and was finally able to relate them to the case of Robert Schmidt.

Schmidt was a 30 year old German living in London who was in need of money to set up a business dealing in animal furs. He decided to make fake gold coins known as sovereigns which he would then mix in with real ones to make them harder to spot. He was not a professional counterfeiter but knew people who were so he thought he would try his luck.

On 11 May 1891 Schmidt went to see a man named Emile Schrier, who worked for the Bank of England as a die-sinker, making the dies which are used to strike coins.

He asked Schrier to make him some dies so he could produce his own counterfeit coins, but the die-sinker was an honest man who, without Schmidt knowing, informed the authorities. Schrier was told to complete the job and set up his ‘client’.

On 5 September the unfortunate Schmidt was arrested as he left the die-sinker’s office with his illegal dies wrapped in a brown paper parcel. The Court found Schmidt guilty and he was sentenced to six years hard labour in prison.

The Vauxhall Coiners

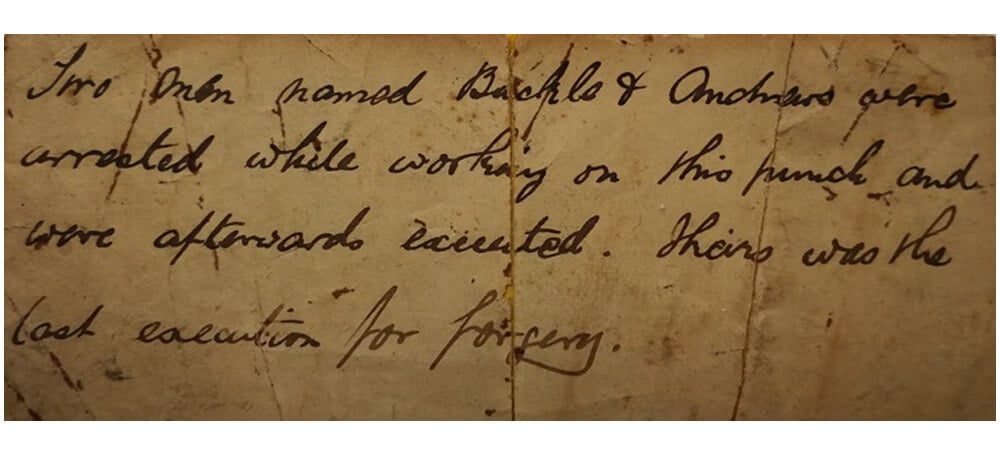

A small sovereign punch from the Museum’s collection is stored along with an anonymous note which reads, ‘Two men named Buckley and Andrews were arrested while working on this punch and were afterwards executed. Theirs was the last execution for forgery.’

This gives us a clue into the case of the Vauxhall coiners, a group of six people, Daniel and Mary Ann Buckley, Jeremiah Andrews, Shadrach Walker, Daniel Pycroft and Mary Ann Patrick, some of whom came to a sticky end!

In the autumn of 1826 the illegal coiners were the subject of a stake-out. They had been seen acting suspiciously, loading and unloading carts and bringing extremely heavy baskets to different locations around London. On 23 December police officers raided houses to find an array of coining tools and thousands of counterfeit coins.

It was suggested, based on the amount of evidence uncovered by the police that the coiners were illegally making around £100 a week, the equivalent of approximately £9,000 today. The entire gang was arrested immediately.

Andrews and Buckley were taken to one of London’s prison ships to await trial. They must have known they were in big trouble as Buckley asked the Principal Officer of the prison ship where he would die and told him that he had already bought a coffin.

At the trial in 1827 three of the men, Pycroft, Buckley and Andrews, were tried for high treason. Pycroft was the only one to call a character witness and it must have worked on the sympathies of the jury as he was allowed to go free. The women involved were only charged with minor crimes, Buckley and Andrews, however, were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. They were executed on 23 April 1827.