Meeting and remembering a man named Machin

By Michael Sedgwick

It is almost a cliché... do you remember where you were when? Well, I remember clearly where I was when I learned of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and heard the terrible news about Princess Diana. Two great, if different, people who contributed enough to the world to deserve coins to be struck for them.

Turn that around and ask what memories stand out most clearly in your mind? Which, among all those special days, were the most special? That brings me right back to coins and to someone whose contribution to that medium will live as long as civilisation: Arnold Machin. Meeting Mr Machin shines like a beacon as one of those most special memories in life’s sea of eventful experiences.

Hard to believe that it is fifteen years ago when, on a stormy, late-winter’s morning, my wife and I drove north to Staffordshire on our way to interview Arnold Machin, wondering how the great man would be. Upon our arrival in the small village, set in the very heart of the countryside, we dropped into the local store for directions. ‘What’s he like?’ I asked. ‘Very pleasant’, came the simple answer to my naïve question. ‘How would you describe him?’ I persisted. ‘In a word, a perfectionist!’ I thought at the time it was probably the answer he thought I expected. Later I realised I was wrong – he was right!

Describing Arnold Machin is just not that easy. It cannot be done in only one word. Indisputably a perfectionist but with a zest for life, and all it offers, which many younger men would envy. A man who, at that stage of his life, was at peace with the world and with himself. His appreciation of line and beauty showed in everything he did, from his exquisitely sculpted figurines, to his special love – landscape gardening.

It was Mrs Machin who greeted us at the door of their redbrick Georgian manor house. An immediately friendly woman, she led us down a long corridor to the large, high-ceilinged living room where Mr Machin was awaiting our arrival. The coral walls played backdrop to so many wonderful pieces of art. A number of well chosen paintings included a magnificent Cooper and a beautiful oil depicting flowers, which we learned later was the work of Mrs Machin – the artist Patricia Newman.

A selection of Arnold Machin’s own work in terracotta and Wedgwood was displayed at various vantage points. The room was well warmed by a roaring log fire which the sculptor prodded fondly from time to time to ensure its good behaviour. After a tour of the room’s major attractions, as we sat down amidst enquiries about the difficulties of our journey, we began to sense the warmth of the man and not just the fire he so proudly stewarded.

The list of questions we had so carefully prepared was at once redundant. The talk was of the house, into which they had moved during the last year or two, and of their old home, a mile or so away, where Arnold Machin had worked with such dedicated enthusiasm to create some incredible garden features. We saw photographs of the wooden bridge built across an eighteenth-century quarry, which he had single-handedly engineered, and of the fountain he had designed and built to set off the finest of views. Modestly, this talented man told us of his current project, the grotto, and offered to show it to us later – ‘if it wouldn’t bore you!’

By the 1940s, Arnold Machin was firmly established as a sculptor, and something that gave him particular pleasure was the fact that several pieces of his work were purchased by his peers: Spring, one of The Four Seasons by the Royal Academy and two pieces, St John the Baptist and The Annunciation by the Tate Gallery. ‘I feel very complimented by that! I’d rather have that than any other kind of praise’, he admitted. ‘In fact, Hugh Gaitskell bought a Wedgwood Bull I had done. One evening we were watching the news on television when they interviewed Mr Kruschev – there on the mantelpiece was my Bull!’

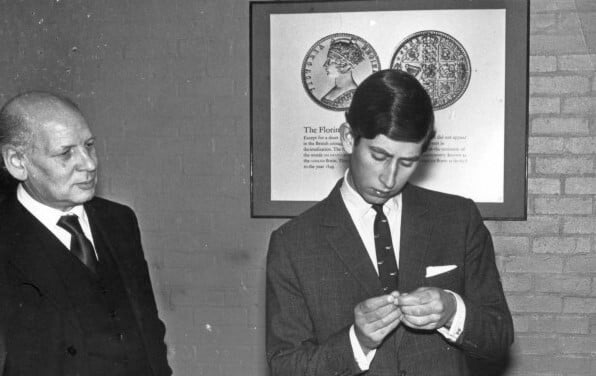

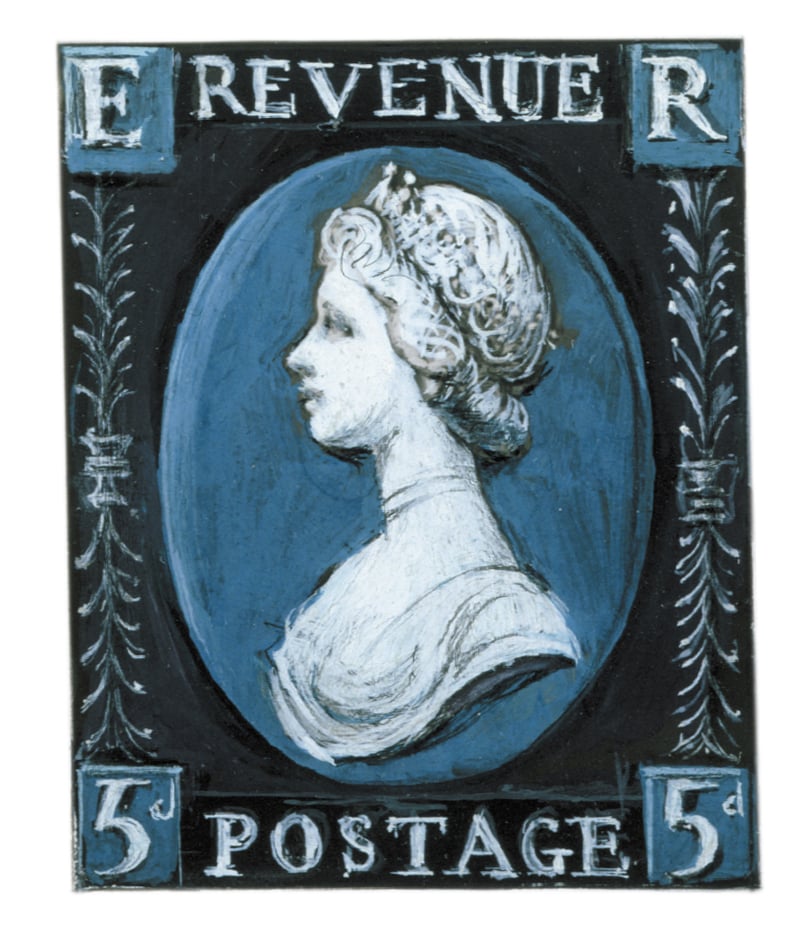

As it turned out, the portrait approved by Her Majesty was first used by the Royal Mint in 1964 on the obverse of coins struck for Rhodesia and Canada, and did not appear on the decimal coinage until 1968. In fact it was the British Post Office which first gave Britain the ‘Machin Head’ when they asked him to rework the effigy for use on Britain’s definitive stamps, the first of which, the 4d olive-brown sepia, appeared in March 1967. Today, more than thirty years and billions of stamps later, it is still with us.

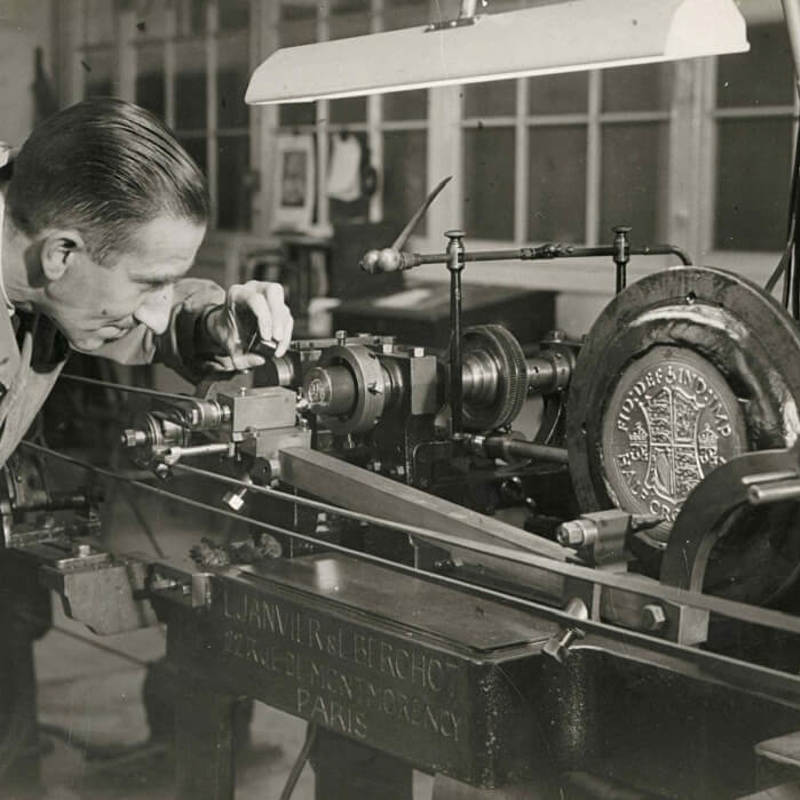

This was the first time that Arnold Machin had worked on a coin, his commercial work having been associated largely with the major British porcelain companies. He recalled that he found it a challenging and different technique. ‘They more or less told me what they wanted and I had to get on with it’, he explained. ‘The problem was to get the relief levels right. It was really very confining!’ He picked up a pad and pencil and began to sketch, indicating what he meant with a few deft strokes. ‘You can’t really model true form – you have to make a depression where the ear comes because that would normally be the highest point, then you work back from there.’

We had to ask the inevitable question. What does it feel like to reach into his pocket and pull out a handful of coins and see his design looking up at him? ‘A lot of people were rather pleased with it at the time, but I’m not very impressed with it. I always find I am so dissatisfied with the end result.’ Pressed a little further however, he admitted, ‘I will say, I can still look at it!’ He went on, of course, to complete other commissions for the Royal Mint – the crowns for the 1972 Royal Silver Wedding Anniversary and the Silver Jubilee of 1977.

Fortified by the excellent afternoon tea which Mrs Machin had provided, we set forth to view his current work of art – the grotto. Leaning into the half-gale, Mr Machin led

us at a brisk canter around the side of the house, through the garden, past the pond, toward a high mound set in the far corner of a walled enclosure. Clambering with remarkable agility, he quickly reached the top, to disappear down a flight of spiral stone steps into the depths of a long series of arches where pools, cascades, lights and ferns were to complete the latest Machin design.

The whole project had been undertaken with the help of ‘a nice chap from the village who comes along and gives me a hand’. Retracing our steps, we returned to the house by way of the new trees Mr Machin had been planting, including a Sequoia Redwood, carefully protected from prying winds and frost. We learned that, in all, five hundred trees were being planted by the same ‘team’ that was building the grotto.

Arnold Machin admired others who have been successful in their particular endeavour and given their all to achieve perfection. He was impressed by the skill and movement of a ballet dancer, the precise angles at which a snooker player hits the ball and the way he is thinking ahead all the time. ‘There’s really only one standard in life, whether it’s washing up or whatever. Do something to the best of your ability. It’s an injury to yourself if you don’t do your best, don’t you think?’

As we left with the invitation to ‘come and see the grotto when it’s finished,’ the sun was dipping to the western horizon. The storm clouds of the day, set against the clearing evening sky, reflected the warm glow of fulfilment we felt in sharing such a memorable time with this mild-mannered, caring man. Now fifteen years later, the sadness of his passing sharpens those memories as if it all happened yesterday. As an avid landscaper myself, falling well short of anything remotely Machinesque, how often his words have echoed in my mind, ‘do something to the best of your ability!’

When the Machin grotto and trees are grown old, the ‘Machin Head’ will live on in proverbial immortality as the legacy of a man who was able to aspire to the loftiest of heights. Even for a perfectionist.

Acknowledgements

Sketch for stamp portrait © Royal Mail Group Ltd, courtesy of the British Postal Museum & Archive

You might also like

Collection in Context

The objects in the Museum each represent a stage in the process of transforming a concept into a coin.

Arnold Machin

Machin designed the royal portrait which featured on United Kingdom decimal coins from 1968-84.