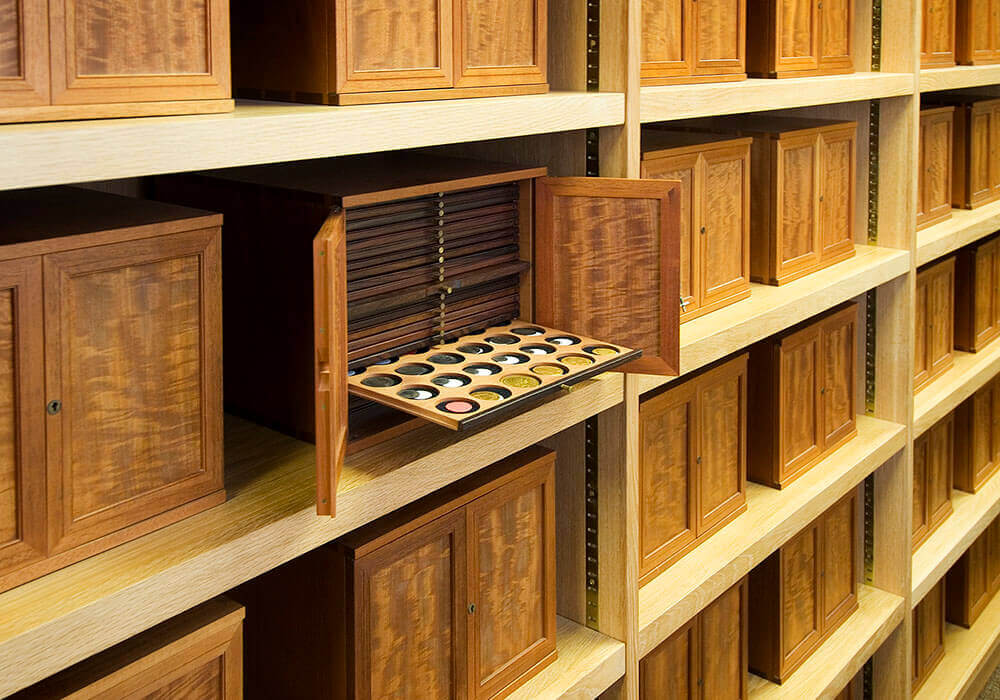

Biblical coins

By Daniel Rignall

The Bible appears regularly throughout the collection of the Royal Mint Museum. It was a popular source for legends and inscriptions on all denominations of coins stretching back to the early medieval period.

Since coins were often a representation of the power of the monarch in whose name they were issued, a biblical verse could serve to bolster a monarch’s authority, indicating their piety and worthiness as a Christian prince. As objects of propaganda, coins that bore carefully chosen biblical legends could also present a political message or remind the owner of the divine institution of the monarch’s position.

Furthermore, these coins tell us something about the biblical literacy of English society. The fact that people carried these Bible verses around in their purses shows widespread familiarity with biblical texts, as well as the relevance of the Bible to matters of the State and to money: people would have had these biblical verses in mind as they made day-to-day financial transactions.

The high point of biblical inscriptions can be seen in the collection of coins from the reigns of the early Stuart kings of England. These were by no means the first kings to employ the Bible on their coinage. Many people throughout the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries would have been familiar with the Latin verse Posui Deum Adjutorem Meum from Psalm 54:4 (I have made God my helper), which was first used on the coins of Edward III (1327-1357). The coins of Edward VI (1547-1553) were replete with biblical verses such as Proverbs 14:27 (The fear of the Lord is the fountain of life), perhaps expected given that his reign saw the high-water mark of the English Reformation.

It was James I (1603-1625), however, who used biblical verses to greatest political effect. For his first coins upon succeeding to the English throne in 1603 he used the bellicose motto of his ancestor James III of Scotland from Psalm 68, Exurgat Deus Dissipentur Inimici (May God arise, and may his enemies be scattered) [see the image below RMM4553]. Such a verse evokes the common tendency to identify England with Israel: the idea that England was God’s new chosen nation, specially protected and blessed. One clergyman, Henry Burton, preached in 1628 that the English should use this motto to fight confidently against foreign enemies, ‘stamping it not in their coyne, but in their colours’. (Henry Burton, Israel’s Fast (London, 1628), 38)

James and his advisors also chose pointed Bible inscriptions to broadcast political messages. Coins could be used to disseminate an image of the somewhat controversial union of the crowns of England and Scotland. The second coinage of 1604 gave James the opportunity to design a long-lasting coinage that would achieve his principal aim of demonstrating his authority as monarch over both kingdoms. The aptly named gold unite, a new iteration of the sovereign that was valid in both England and Scotland, bore the impressive legend Facium Eos In Gentum Unum from the Book of Ezekiel (I will make them one nation). The silver crown, half-crown, shilling and sixpence – more accessible to the general public – carried instead Matthew 19:6, Quae Deus coniunxit nemo separet, (What God has joined together, let no-one separate) [see the image below RMM4542]. This displayed James’s belief in the providential nature of the union and rebuked anyone who sought to undermine it. It was the verse that James quoted in his first speech to the English parliament, and, to the general population, this verse would have been extremely well known as the climactic moment in the wedding service, indicating the presentation of the union as a marriage between nations. (Bruce Galloway, The Union of England and Scotland, 1603-1608 (Edinburgh, 1986), 59-60.)

Such political usage of the Bible was common in the seventeenth century. It was not unusual to use biblical language, stories and allusions to describe or debate contemporary political events. This was the period when the Bible was most accessible and comprehensible to the general public: the Authorised or King James version was produced in 1611, leading to a vast increase in familiarity with, and interest in, the Bible. It was seen as an authoritative – and often radical – political text, with things to say about the rights and duties of kingship, the rule of law, and the limits of a subjects’ obedience. The Bible was therefore particularly utilised in times of crisis: much of the political thought behind the Civil Wars was drawn from the Old Testament, for example.

While Charles I (1625-1649) initially eschewed direct biblical quotations on his coinage (instead preferring the more personal motto ‘I reign under the auspices of Christ’), he returned to his father’s Exurgat inscription once hostilities against Parliament began. These coins [see the image above RMM5117], struck at the King’s wartime mints in Shrewsbury and Oxford, combined the combative Psalm verse – a threat against his adversaries – with the famous irenic ‘Declaration’ to protect the Protestant religion, the laws of England and a free parliament. Such a conflicting message is reflected in Charles’s obverse portrait, where he carries both a sword and an olive branch. Given the context of the political use of the Bible in seventeenth-century England it is perhaps unsurprising that it is the biblical half of this message that is the most incendiary.