Wonderful Angels and the Healing Touch

by Beth Seaman

It may seem surprising, but coins have historically been used in medical practices in England, particularly as a method of healing and protection against disease. From the late medieval period, around 1470, gold coins called “Angels” were used in a healing ritual known as a “Touching Ceremony”. During this ceremony, the monarch would pass on some of his or her God-given power to cure ordinary people. To do this the coin would be touched and often pierced, then hung around the person’s neck to continue to protect the wearer against disease.

The disease which was thought to be cured by the monarch’s touch was called the King’s Evil, or scrofula, but today this is known as tuberculosis of the neck. Scrofula would often go untreated and cause sores on the skin, which were embarrassing for the sufferer but not fatal. The King or Queen would often touch the sores as prayers were read aloud. Some monarchs made the sign of the cross with the coin over the patient’s sores, then hung the Angel around their neck with a white silk ribbon. Scrofula can heal naturally, and sudden improvements in symptoms occurred frequently, so people tended to assume that spontaneous healings were due to miraculous or magical interventions caused by the coin.

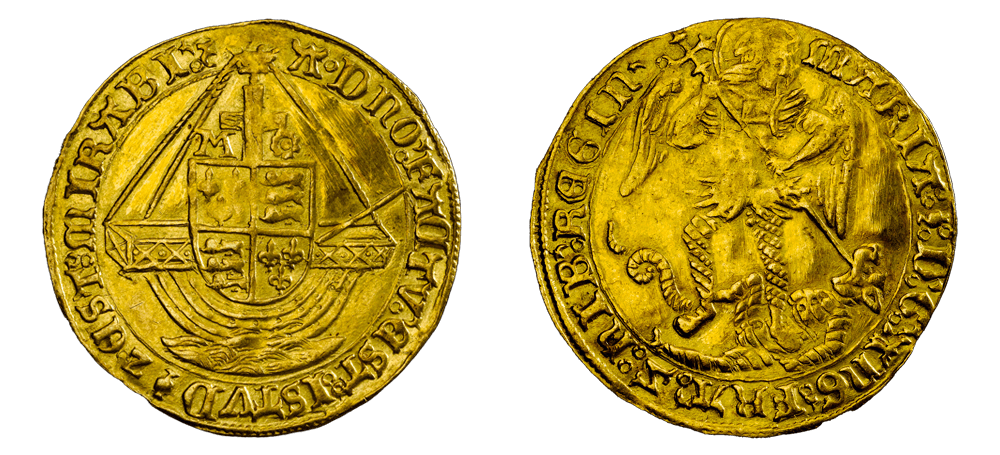

The Angel was so named because it showed a design of the Archangel Michael spearing the dragon of evil on the obverse (front) of the coin. The reverse side tended to picture a ship with a cross in the mast, and symbols associated with the reigning monarch at the time. The healing ceremony was a big event, meant to showcase the divine power of the monarch and to establish good relations with the public. It was believed that only the true ruler of the country had the power to heal, therefore it was a helpful way to reinforce the validity of the current royalty, during periods of political unrest such as during the Wars of the Roses.

The “Touching Ceremony” and the Angel coin were seen as a wondrous display of the King’s ability to channel divine power and reflected a historical association of gold and silver with the ability to heal. The power of the Angel coin would have had several layers of meaning in this period. Firstly, gold itself is an indicator of wealth and upstanding social status. As well as this, the Angel exuded religious significance through its imagery of divinity, and the touch of the monarch. The obverse side of the Angel often featured a biblical inscription in Latin, again meant to reinforce the religious power of the object. These factors meant that the item had a marvellous quality to it and showcased the wonder of the natural world, the wondrous potential of wealth, and divine wonders produced by God. Edward VI, who first ordered the Angel coin to be struck in 1465, included the legend or inscription: “per crucem tua salva nos chr redempt”- this translates as “by thy Cross save us Redeemer Christ”. The phrase reflects an association between religion and healing, and by being included on the coin with the monarch’s initials, it reinforces the idea of the King having marvellous divine power.

Changes to the Angel coin over time give an idea of the personal, religious and political leanings of each reigning monarch. For example, Mary Tudor (who ruled between 1553-1558) was said to have been very serious about the ceremony and included on her Angels the phrase: “a domino factum est istud et est mirabile in oculus nostris”, which is translated as “it is the Lord’s doing and it is marvellous in our eyes”.

As a devout Roman Catholic, she was a firm believer in the divine marvel of the ceremony. She was also one of the monarchs who made sure to touch the patient’s sores with her own hands, and to make the sign of the cross over the wounds. By contrast, when James I ascended the throne in 1603, he was reluctant to carry out the ceremony at all as he believed it was superstitious. However, as the tradition was popular with the English public, and helped to reinforce the royal image, angels were struck during his reign.

The Angel coin is an interesting example of how medicine interacted with everyday objects throughout history. It shows the way in which ordinary people thought about healing, religion and royalty, and offers an insight into how monarchs tried to manage their relationship with the public during times of political and religious turmoil.

Beth Seaman is a PhD student at the University of Birmingham, whose research analyses the development of popular medical knowledge in late medieval-renaissance England. This placement was generously funded by Midlands4Cities Doctoral Training Partnership.