Double Portraits on the coinage

In recent times double portraits have been used on a handful of crown coins issued to celebrate royal occasions, namely the marriage of the Prince of Wales and Lady Diana Spencer in 1981, the Golden Wedding of Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip in 1997, the Diamond Wedding in 2007 and the marriage of Prince William and Miss Catherine Middleton in 2011. But it is necessary to go back several hundred years to find examples of this type of design on British coins intended for general circulation.

Philip & Mary shilling, 1554

Philip & Mary

The first English coins to bear a double portrait were issued during the reign of Mary I after her unpopular marriage to Philip of Spain. Although regal power remained vested in the queen, Philip’s effigy was included on issues of shillings and sixpences. The two portraits were shown facing each other after the style of the gold coins of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain produced half a century earlier. In keeping with the conventions of a male-dominated society, Philip was afforded the primary position to the left of the design despite his lesser constitutional status.

Coins of Mary’s reign continued to circulate until the Great Recoinage at the end of the 17th century. The apparent affection between the royal couple as depicted on the coinage moved the English poet, Samuel Butler (1612-80), to write the following epigram:

Still amorous, and fond, and billing

Like Philip and Mary on a shilling.

Such romantic sentiments were far removed from those Protestant contemporaries who suffered at the hands of the queen. Bishop Hooper was burned at the stake in Gloucester on 9 February 1555, and his widow would later describe the portraits on the coins as ‘the effigies of Ahab and Jezebel’.

Mary Queen of Scots

It was not long before the fashion for facing portraits extended north of the border to the independent Scottish coinage. Mary Queen of Scots was brought up at the French Court and in 1558, at the age of 15, was married to Francis, Dauphin of France. An issue of Scottish gold ducats followed shortly afterwards which included the portraits of the royal couple. A very limited number of pieces were struck and only a few are now known to exist. Following the death of Francis in 1560, Mary decided to return to her native Scotland. The ill-fated marriage with Henry, Lord Darnley took place five years later and a small number of silver ryals bearing facing portraits was issued into circulation. Francis and Henry both appeared to the left in their respective double portraits, conveying the same sense of masculine precedence as in England.

Williams & Mary five guineas, 1692

William & Mary

It was more than a century before the Glorious Revolution resulted in the next example of a double portrait on circulating coins. In 1688 a group of notable English Protestants invited William of Orange to invade and secure the succession for his wife Mary, the Protestant elder daughter of James II. William landed at Torbay on 5 November and, after a brief period of uncertainty, James II fled to France. It was widely believed that Mary alone would assume the throne but, having come this far, William had no intention of accepting the position of consort. In the face of his threats to return home to the Netherlands, the opposition in Parliament crumbled and on 13 February 1689 William and Mary were declared joint monarchs.

With the accession of two sovereigns, it became necessary to prepare a double portrait for the coinage and this took the form of conjoined effigies rather than the facing type of Philip and Mary. The classical style was in the ascendancy at the end of the 17th century and it seems likely the choice of design was derived from conjoined portraits on Roman coins, such as those of Mark Antony and Octavia, and Claudius and Agrippina. Despite the equal constitutional status of William and Mary, regal power was exercised almost single-handedly by the king and perhaps for this reason his portrait was afforded the foremost position in the design.

Royal Weddings

The circumstances surrounding the use of double portraits in early-modern Britain serve as a reminder of the intense political manoeuvring associated with royal marriages at the time. Both Philip of Spain and William of Orange married English brides in order to secure military co-operation against France.

The first marriage of Mary Queen of Scots was intended to strengthen the auld alliance between Scotland and France, and her second to Lord Darnley, the great-grandson of Henry VII, was motivated by a desire to shore up the claim of her descendants to the English throne. Mary’s marriage with Darnley may have been hugely unsuccessful in every other way but, as hoped for, their son James was destined to become king of England as well as Scotland.

Needless to say royal marriages are now no longer governed by the same kind of political considerations. In this regard the double portraits on recent commemorative crowns have provided a welcome opportunity to celebrate the much more personal unions of queens and princes today.

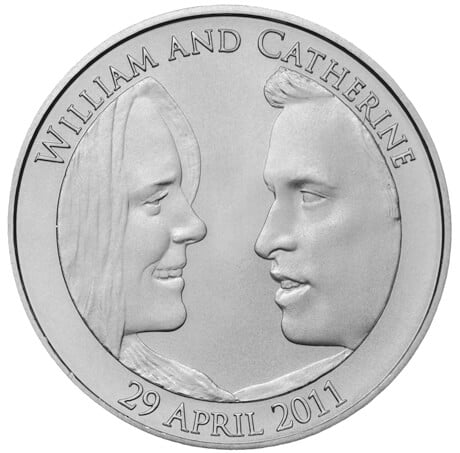

Royal Wedding crown 2011

You might also like

Demise of the Florin

When the old-sized 10p pieces ceased to be legal tender at the end of June 1993, florins of the former £sd coinage were removed from circulation.

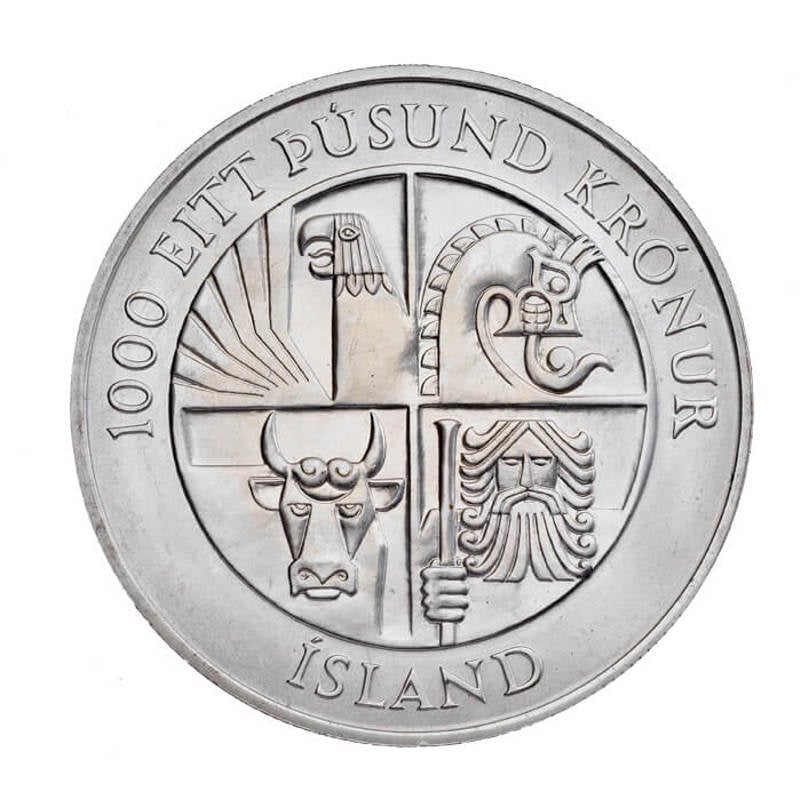

Coins of Iceland

The origins of Iceland’s relationship with the Royal Mint may be found in the Second World War.

Arnold Machin

Machin designed the royal portrait which featured on United Kingdom decimal coins from 1968-84.