Charles II

Summary

The reign of Charles II saw a great leap forward in the technology of minting and the aesthetic possibilities of the coinage. The Restoration of the Monarchy was a time of great change, but also a return to the stability of the past, all of which is reflected in the nation’s coinage. It is during this period that the process of coin manufacture is finally mechanised, replacing the old method of hand-striking and paving the way for more intricate designs and security features. The guinea is introduced as a new gold coin, and depictions of Britannia reappear on the coinage for the first time since that of the Romans.

Mechanisation

During the reign the Mint is based within the Tower of London, occupying the space between the inner and outer walls of the Tower. This was a period of great change for the organisation owing to mechanisation of the production process, and the planning involved to enable the installation of the new machinery would have presented a significant logistical challenge. Space needed to be created for the introduction of horse-drawn rolling mills, edge marking machinery and for the large screw presses that would have been used to strike the coins. Moving from hand striking to striking by machine created considerable disturbance, and building work was required to accommodate the change with some of the existing residences in the Tower being turned over to house the new machinery.

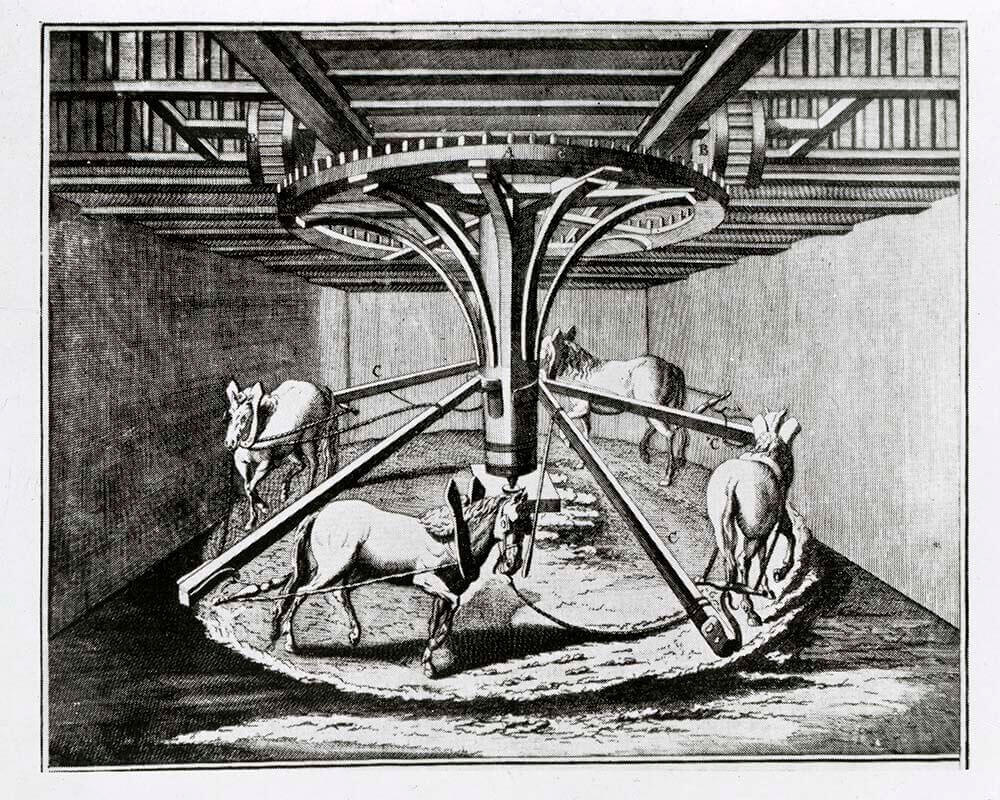

17th century French engraving of a horse-drawn rolling mill.

This equipment was the responsibility of the Frenchman, Pierre Blondeau, who had been brought over to supervise its installation and to effectively act as engineer to the Mint. Whilst alive he also operated the machinery used to apply edge lettering and milling to the coins. Despite this equipment openly being shown to visitors in Paris and described in print, Blondeau insisted that an oath of secrecy be taken by the small number of Mint people that had knowledge of its operation, a practice that was religiously continued until as late as 1811.

The machinery was still labour intensive, a team of six horses were required for the rolling mills – four to operate them and two to provide for rest rotation. Furthermore the screw presses required strenuous labour, a team of seven being assigned to a press, of whom three rested whilst four operated the press in twenty minute spells.

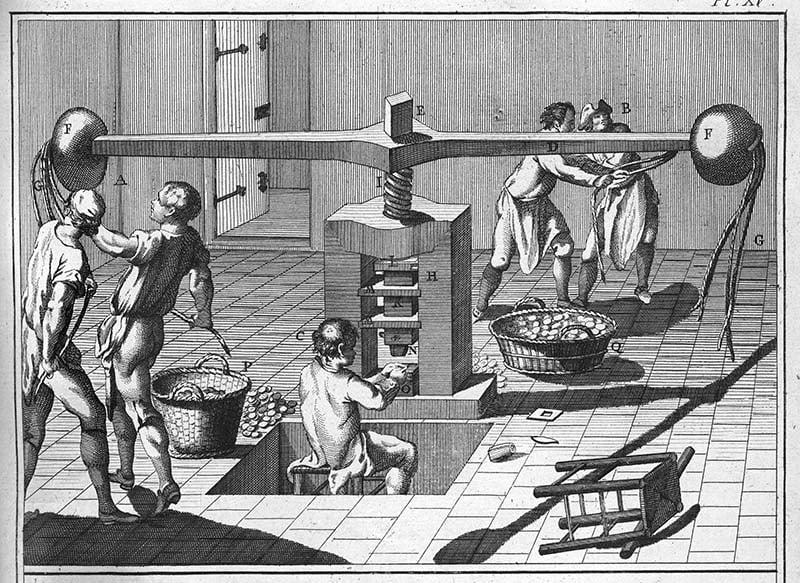

17th century French engraving of a screw press.

Production rates were rapid given the technology available and coins were struck roughly at a rate of 30 a minute. Blanks were added to the press by a young moneyer seated at eye level with the dies, and he would be responsible for flicking the finished coin away with his middle finger whilst using his thumb and index finger to add a fresh blank. Injuries in this job were common place and centuries later when Pistrucci arrived at the Mint he observed that most moneyers had lost one or more finger joints.

Machine struck coins had a distinct advantage over their hammered counterparts, creating a thicker and more uniform coinage as it was possible to strike blanks with a higher tonnage. In addition to producing pieces of a better quality, it enabled the introduction of important security features such as milling and edge lettering. As a result, the coins were harder to counterfeit and these features also prevented the coinage from being clipped; a dishonest process whereby a small amount of gold or silver was shaved from the edges.

Installation of the new machinery was sufficiently advanced for production to begin in February 1662 on the gold coinage, with production to the other silver coins being rolled out over the following year or so. Hammered coinage production did not cease immediately as demand was so acute that both methods were used simultaneously for a short while.

For a contemporary account of mechanised production, Samuel Pepys visited the Mint on Tuesday 16 May 1663 and detailed the process.

Gold coinage

It was during the reign in 1663 that the guinea was first introduced. Initially beginning life as a 20 shilling coin, rather than the 21 shillings value it would acquire in 1717, the full range of gold coins struck throughout the period included a half guinea, two guinea and five guinea pieces.

Charles II guinea family. Five guinea piece (RMM627), two guinea piece (RMM629), guinea (RMM634), half-guinea (RMM639)

The gold for the production of these coins was originally transported by the Africa Company from their trading along the Guinea coast of Africa and the coins name reference this. Owing to the Africa Company links, some of the pieces in the guinea family bear the elephant or elephant and castle mark which was the badge of the company. As an added security measure, the five guinea pieces features the edge inscription DECUS ET TUTAMEN, which translates as ‘an ornament and a safeguard’ and would later be reused on the £1 coin introduced in 1983.

Edge inscription on the five guinea piece (RMM627)

Silver coinage

The silver coinage adopts a denominational structure which is generally unchanged for many centuries and the denominations in use would have, by and large, been familiar to people in the years immediately prior to decimalisation in the 1970s. The first machine struck half crowns and shillings began production in 1663 and this was followed by the smaller denominations - sixpence, fourpence, threepence, twopence and penny – over the next decade or so. The crown and half crown feature the same inscription as the five guinea piece (DECUS ET TUTAMEN) accompanied by the regnal year, which in Charles II’s case is calculated from the death of his father in 1649 rather than the date of his restoration.

Charles II silver coinage. Crown (RMM656), half-crown (RMM666), shilling (RMM685), sixpence (RMM691), fourpence (RMM697), threepence (RMM707), twopence (RMM710), penny (RMM717)

As with the gold pieces, silver displayed marks to denote the source of the metal from which they were produced. In addition to the elephant and elephant and castle marks for the Africa Company, the Welsh plumes were added to denote mines in Wales and a Rose for silver extracted from the West of England.

Copper coinage

Although state sponsored copper pieces had been struck in earlier reigns these did not have legal tender status and the first official copper coinage was not produced until the reign of Charles II. Numerous pattern pieces for this new coinage were struck throughout the 1660s and many of these depict the figure of Britannia, the image of which was said to have been based on one of the King’s mistresses, Frances Stuart, Duchess of Richmond. It was not until 1672 that official pieces were struck for circulation, with the new halfpennies and farthings retaining the use of the Britannia design and beginning the long tradition of her appearance on the coinage. The Royal Mint had no prior experience of working in copper and was ill-equipped to do anything other than strike the new coins. Copper blanks therefore had to be purchased directly from Sweden for these new coins, a process which led to a delay in production owing to the difficulty of importing blanks through the winter months.

Charles II copper coinage. Half-penny (RMM719), farthing (RMM729)

Tin coinage

In order to stimulate the Cornish tin industry it was proposed that halfpennies and farthings be made from English tin. This replaced copper in 1684 but, as tin was readily available and easy to work, a small plug of copper was inserted into the pieces to make them harder to counterfeit.

Engravers

Thomas Simon, the Chief Engraver during the Commonwealth period and Oliver Cromwell’s protectorate, continued in post and was joined by Thomas Rawlings, the itinerant engraver who had produced tools for the various emergency Royalist mints during the Civil War. Rawlings may have had some involvement in the first hammered coinage dies of Charles II but in the 10 years till his death in 1670 he did no coinage work. Simon produced the Great Seal of Charles II, to add to his numerous other Great Seals, and engraved the tooling for the first hammered coins of the reign. His days as engraver of the coinage were however drawing to a close. Soon after the start of 1662 a Flanders family of engravers, John, Joseph and Philip Roettier, who the new King had become acquainted with during his time in exile. They were summoned to England and ordered to prepare designs and trials for the new milled coinage. Simon was also instructed to prepare designs and trials, but it appears that he only got as far as initially producing designs owing to the pressure of work in preparing tooling for the new machine struck 20 shilling gold pieces. Difficulties in producing dies of sufficient quality for these pieces distracted Simon, and the Roettiers gained an advantage by submitting trial pieces of their designs which were ultimately approved for production by the King. Until his death in the Great Plague of 1665, Simon was confined to a minor role in engraving dies for Maundy pieces and it was John Roettier that was the main engraver during the reign. Bitter at being side-lined, it was in this context that Simon produced his famous Petition crown with its extraordinary double-line of edge inscription to showcase his skill and offer a direct petition to the King for re-instatement in engraving the coinage.

Charles II crown (RMM650)

Collection

Charles II counterfeit crown

The coin illustrated here purports to be a crown piece of Charles II dated 1672 but is obviously counterfeit.

Portrait punch of Charles II

From the reign of Charles II there was a more systematic approach to retaining tools at the Royal Mint which finds early expression in a series of portrait punches.

Thomas Simon collection

The work of the engraver Thomas Simon spanned a turbulent period of England's history.